STOP PRESS! Go HERE to order our great new field guide, ANTS OF SOUTHERN AFRICA, in press and for immediate delivery by airmail or courier ...

NB This site is under reconstruction. We are redesigning the site with a number of inputs from our book, Ants of Southern Africa. While reconstruction is in progress some links may not work properly – please be patient!

INTRODUCTION

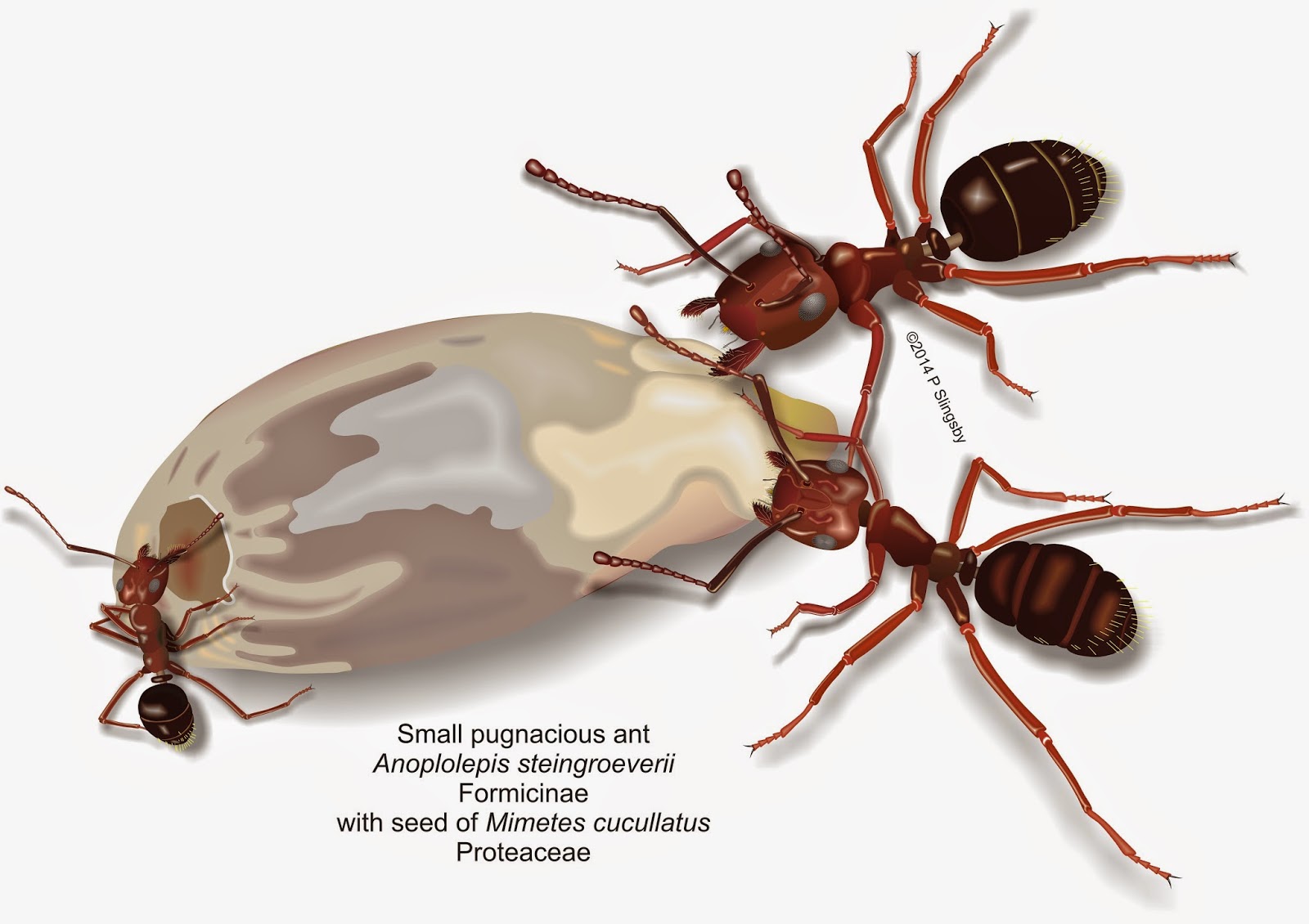

We’ve put this website together to help anyone interested in the natural systems of South Africa to identify these tiny but fascinating animals. There’s more about recognizing ants in the pages below, with some fairly basic stuff about these insects and their biology. Our ants are as much a part of our fantastic wildlife heritage as lions and rhinos, fish eagles and blue cranes, mighty yellowwoods and king proteas. The ecological role they play is immensely important for the health of our natural systems. Ants are essential seed-distributors to thousands of charismatically-beautiful fynbos plants; they are pollinators and recyclers, too, and also vectors in the spread of many plant predators. However, just as there are plant invaders that threaten our natural systems there are insect invaders, too, and we’re keeping an eye on some pretty murderous invasive ants.

We’ve based this revised site on our Field Guide, ‘Ants of Southern Africa’, the first and only field guide to our local ants; see link above if you would like to buy one online.

If you have any info, queries or comments please use the Comments box below.

Introduction to ‘Ants of Southern Africa’

Ants grabbed me when I was but a spotty teenager. Some grabbed me literally with snapping mandibles, and I discovered that they can seldom really hurt you. Years later, when my own barefoot kids would start hopping around on the sandy veld paths shouting ‘Biting ants!’, I’d encourage them to stand quite still and tell me, honestly, whether the ants were hurting them.‘No,’ they’d reply, after a moment or two, ‘but they tickle!’

Pugnacious ants, Anoplolepis custodiens, have held few fears for them ever since. And me? They’re my favourite ants. Bold, tiny little girls, quite unafraid of human beings.

Most people, told that I like ants, ask me at once how to get rid of them. The answer is, of course, ‘you can’t.’ You can soak your kitchen, your fruit trees, your garden beauties with litres of insecticide, but after a few days the ants will be back. It’s estimated that 20% of the dry land biomass on our planet consists of ants. Think about how many humans live in your house, now estimate the number of ants. Scary? Not really. They collectively destroy more insect ‘pests’ than you ever could do with a spray can. They outnumber us by uncountable trillions; we will never get rid of them.

In 1961 the great entomologist Sydney Skaife published a book titled The Study of Ants. It was the first-ever ‘citizen science’ book about Southern African ants; Skaife’s opening lines read: “Ants ... have been collected, preserved and described in minute detail, and classified in families, genera, species, subspecies, races and varieties, and they have been given long polysyllabic names. They are abundant almost everywhere, of considerable economic importance, and offer ... challenging problems to entomologists, yet few are engaged in the study of these fascinating little insects, apart from the description and naming of them.”

I was given a copy of this wonderful book at the age of 15, and soon I was irritating my family with colonies of ants in plaster nests on ant-tables, using Skaife’s recommended methods. The ants were forever escaping, or being attacked by Argentine ants, or having other interactive adventures with my family members. Within a couple of years I was persuaded to donate my thriving, seething masses to the great Skaife himself. And that led to several visits to his laboratory at Tierboskloof, in the mountains above Hout Bay.

Skaife was a founder of the Wildlife Society of SA (WESSA); almost single-handedly, he created the Cape of Good Hope Nature Reserve – the best-preserved section of the Table Mountain National Park. A natural teacher, he and his ants had me in thrall, even though I never followed him into formal science.

By 1981 we were living in Kleinmond. Professor-to-be William Bond had become a close friend; I was trying to learn everything I could about fynbos and the Kogelberg, the veld where I had collected my first ants, à la the methods of Skaife. One day William showed me some seeds with a tiny white attachment. ‘Rudolf Marloth, a citizen botanist, wrote that at least six fynbos species have seeds like this, that deliberately attract ants; the ants bury the seeds, safe from fire,’ William explained. Within a few weeks we had identified over 2 000 fynbos plants that use ants to bury their seeds ... academic papers followed, of course.

By 1991 I had put together a little black and white booklet, Ants of the Western Cape; Hamish Robertson of Iziko museums, another great entomologist, had helped me correct my worst amateur bloopers. The second citizen science book about Southern African ants was born. It was a very poor replacement for Skaife, though.

Twenty-five years later that was still all there was. There were two books, both out of print. There are a few relatively academic websites that, valuable as they are, specialise in pictures of very dead ants. They hold almost no information about their habits, their nature, their basic biology, and they all have inadequate and often incorrect information about their distribution. In 2016 the experts Brian L. Fisher and Barry Bolton published their impressive Ants of Africa and Madagascar: an academic book that will take your interest to a higher level, but that has little info about your local species.

In 2014 I joined Tony Rebelo’s iSpot (he’ll say it wasn’t his, but don’t believe him – in those days it was) and I soon found that there were lots of people who were photographing ants and posting iSpot observations about them – amongst lots of other extraordinary things. But there’s the rub: many of them could not identify their ants. There was simply no ‘citizen science friendly’ guide to our very rich ant fauna, and there appeared to be no one prepared to put one together. Yet here were nearly 2000 photographs of ants from all over Southern Africa taken by iSpotters, many of them of a very high quality. Here was a resource that should be presented to a wider public; what better way than a printed field guide.

Naïvely, I grabbed the tiger by the tail. Distant academic snarls suggested that such a thing should not be done without an expert’s benign, watchful eye. Yet even the experts, even the world’s greatest, do not agree upon the identification of species in some of the largest and most prominent of Earth’s genera of ants. They can’t identify them – at least, not to every other professional’s satisfaction – without lots of interesting, stimulating disagreement.

More than fifty years ago Skaife recognised the potential contribution to his discipline of citizen science – all science, after all, started with ‘citizen science’, with our human curiosity directed at the world around us. So, I have plunged in where greater angels have feared to tread. There are errors in this account: many genera are screaming for taxonomic revision. Here and there I might have a wrong photo, but please bear with me: precise help has not been easy to find. I absolutely acknowledge that many ants – the tiny ones, the LBJ’s of the ant world, especially – can only be identified under high-powered magnification, equipment that is not found in everyone’s kitchen.

But there are hundreds of others – who could mistake the magnificent hairy, tawny gaster and gaping jaws of a Karoo balbyter? Anyone with good vision (they are all small), good sense (the subfamilies are pretty easy, actually) and enthusiasm can learn about ants and their world; the more enthusiastic citizen science we can focus upon ants, the more – much, much more – we’ll learn about these extra-ordinary insects, their habits, behaviour, what they eat, how they interact with other organisms, and especially where in our Southern African region the different species are to be found. That’s the info the taxonomists trying to ID them need, and that’s how we can help them.